Rainier:

Kautz Glacier

14–16 August 1970

Basic Climbing Course students Chris and Kathy decided to join me for a

climb of Mount Rainier rather than attend the final session of the

course for a climb of Mount Baker.

I was supposed to be assisting on the Baker climb;

it would have been a repeat of

unpleasant memories:

same instructor,

same route.

The instructor excused me from the duty.

We arrived at 7:00pm on Friday to get checked out by the ranger.

At that time the rangers were strict;

they checked both the equipment and qualifications of climbers.

Our equipment was fine,

but I could see the ranger frown as he read Chris and Kathy's

qualifications from their application forms.

There was not enough room on the form for all my glacier climbs,

so I listed the most challenging ones I had done,

including an ascent of Rainier via the

Nisqually Ice Fall.

When the ranger got to my form,

he smiled and said

“Have fun!”

The rangers are not so diligent now,

but at the time of this climb the requirements were outlined in the 1961

edition of Fred Beckey's

“Climber's Guide to the Cascade and Olympic Mountains of Washington”:

All climbers are required to register at the nearest ranger station

in the park.

Such registration includes a check of the equipment and climber's

experience on similar glacier-covered peaks.

Equipment must include rope

(climbing rope and rope slings for crevasse rescue),

ice axes, crampons, sun glasses, boots, wool clothing, parka,

mittens, sleeping bag, first aid kit, flashlight and adequate food

for a two-day trip.

There were apocryphal tales of rangers propping ice axes against a rock

and breaking them by jumping on them if they did not think you or your

equipment were up to the climb.

The route to the Kautz high camp requires roped glacier travel and some

steep snow slopes.

By hiking in the late evening we got a head start,

making a bivouac at 6,200 feet next to the Nisqually Glacier in fine

weather at 9:30pm.

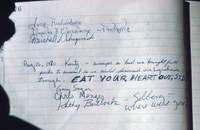

The accompanying picture,

taken from the starting point of the climb near the Paradise parking lot,

shows the route.

The large feature to the right of the prominent trees is Gibralter Rock.

The

Nisqually Ice Fall

is just left of the the prominent trees;

the Nisqually Glacier continues into the valley hidden by the trees.

After crossing the lower Nisqually Glacier and the Wilson Glacier

the route ascends a snow field known as The Turtle

(which looks like road kill in this picture).

The high camp is at 11,300 feet next to the tongue of the Kautz Glacier.

The red line shows the route.

The top of the lower line ends where

“high camp”

is.

The break in the line shows where we traversed into the chute of ice

(aka headwall)

that is the lower tongue of the Kautz.

On Saturday,

we started across the Nisqually and up the Turtle.

We arrived at high camp at 3:00pm,

having gained over 5,000 feet of elevation to spend the night at 11,300 feet.

This camp is affectionately known as

Camp Hazard,

presumably after

Hazard Stevens,

a member of the party to first ascend Rainier to the summit in 1870.

But the overhanging ice cliffs of the Kautz Glacier suggest another reason

for the name.

While Chris and Kathy organized their gear and prepared dinner,

I scouted out the traverse through a gully of loose rock we would have

to negotiate in the dark come the next morning.

A very large boulder blocked the way and as I held onto it to make my

way around,

it came loose and threatened to roll over me.

I scrambled up the rolling boulder and managed to get over it and jump

into the gully.

The boulder rolled for hundreds of feet down the mountain.

I continued the scouting and did not mention the incident to Chris or

Kathy when I got back to camp.

I did not remove my

climbing knickers

until I got home;

when I did remove them,

my legs were badly scratched and the insides of the knickers were

covered with blood.

Over dinner,

I convinced Chris and Kathy that the portion of the glacier I had seen

on my scouting expedition was going to be a challenging climb and we

should take full packs over the summit then descend the Ingraham route

rather than try to descend back to our high camp to collect our gear and

then retrace our route across the Nisqually and hike uphill to get back

to the car.

Carrying full packs would make the climb to the summit more physically

challenging,

but we were already at one of the highest camps on the mountain and had

“only”

3,100 feet to go.

If we gave up,

there was no alternative escape route other than retracing our steps;

on the other hand,

if we made the summit the easier descent would more than justify the

effort.

Another party arrived at 6:00pm;

they planned to leave for the summit at 3:00am and return to Camp

Hazard to spend another night on the mountain.

We woke at midnight and left at 2:00am to start our climb;

preparations took some time because we had to completely pack up camp as

well as get some warm food into us.

We crossed the gully and started up the chute in the tongue of the

Kautz.

The

nieves penitentes

(aka sun cups)

were extreme:

often measuring 5 feet from the bottom of the cup to the tip of the

penitente.

There was a full moon making the penitentes seem to glow,

giving the whole scene a surreal bluish appearance.

Years later,

seeing the

Taj Mahal by moonlight

would remind me of this climb.

We proceeded through some very steep sections of the sun cups with the

confidence that if someone were to fall,

the rope would be caught on the penitentes and stop the fall quickly.

The going was similar to class 4 on rock as we climbed from one sun cup

to the next.

As the slope eased,

we continued on until I noticed that the bottom of the sun cup in front

of me was missing.

The snow had melted what would otherwise be a snow bridge just enough to

expose a crevasse,

leaving a lattice of bottomless suncups as the

“bridge!”

I started to turn to my right when I noticed the sun cup there had no

bottom;

the same was true if I tried to go left.

I yelled to everyone to stop and back up slowly.

After that,

we proceeded with great caution,

testing the bottoms of sun cups before venturing into them.

The sun cups disguised the crevasses so we often could not see them until

we were literally on top of them.

Unfortunately,

climbs of Rainier start well before sunrise,

making it difficult or impossible to get pictures of the most

challenging parts of the climb.

Waiting for sunrise can make the climb more difficult and/or dangerous,

as the sun makes the snow slushy,

snow bridges less strong,

frozen rocks break loose and ice cliffs calve.

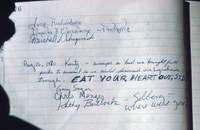

In this picture Kathy appears unhappy that I am going downhill,

a necessary maneuver to get around a crevasse.

The going is not as steep and the suncups are not as deep as what we had

negotiated in the dark.

It took us 3½ hours to gain the first 1,000 feet through the

technical difficulties coming out of high camp.

Above that,

the sun cups were less severe and the going got easier.

We encountered one final huge crevasse that took a very long traverse to

circumvent.

The challenge as we approached the summit was 70mph winds that blew pumice

dust into our eyes and sometimes made balance tenuous.

At the summit we signed the register with a special note to Solberg,

a friend of Kathy's who was supposed to be climbing Rainier by a

different route that day.

We also left a note for Sid,

who had chosen to go with the Basic Climbing Course to Mount Baker

rather than accompany us.

We later found out that they did not make their summit due to poor

weather –

is it possible the instructor was much more cautious this time?

While I was sheltering from the wind with other climbers,

another climber kept looking my way.

With all the cold weather gear covering our faces it was hard to tell

who was who.

He finally asked

“Are you Gary Sager?”

It turned out to be

Bruce Carson.

He was leading students from another climbing course up the Ingraham

route.

He signalled me to come over and look into his pack;

inside was a 15 pound watermelon he had intended to share at the summit.

He said:

“The hell of it is that it's frozen so I'll have to carry it down.”

Chris,

Kathy and I roped up after an hour on the summit and headed down the

Ingraham

(aka tourist)

route with them in the lead.

There was a deep trough made by all the climbers trudging up and down

the mountain so it was impossible to get lost even though I had never come

up the route and only gone down it

once before.

Every once in a while we would come to a crevasse 2-3 feet wide and hop

over without stopping,

passing others who were belaying the jump;

of course,

we maintained just enough slack in the rope and were prepared to do an

ice axe arrest

should one of us miss the jump.

Chris and Kathy were now old hands and totally unimpressed with the lack

of route-finding challenges and the

“miniature”

crevasses.

This may be the

“tourist route,”

but it can still be

deadly.

As we walked into Camp Muir at 10,000 feet,

a ranger was checking in climbers coming from the summit;

he took one look at us and said

“You didn't come up this way!”

His tone seemed mildly accusatory;

we explained our decision-making and,

having satisfied him,

were soon on the way down.

Back at the Paradise ranger station,

we checked in to give our assessment of the route.

We were the first party to complete the route in over a month so the

rangers appreciated some updated information.

The rangers also told us the party who joined us at Camp Hazard had turned

back.

Although the Kautz route is

rated as Grade 3,

I found the conditions more challenging and more fraught with objective

danger than we faced climbing

Liberty Ridge.

The steep section up the tongue chute was certainly more than just kicking

steps and our inability to see crevasses in the sun cups meant we often

wound up dangerously close to them.

On the other hand,

on Liberty Ridge we were blessed with unusually favorable conditions and

that route certainly presents much more dramatic scenery.

One of the students in the climbing course was a reporter for the

Seattle Times.

I invited her on the Kautz climb,

but she felt it necessary to stay with the Basic Climbing Course as she

was going to write an article about her experience in the course.

Since the Mount Baker climb was unsuccessful,

she expressed regrets at not being able to chronicle an ascent of one of

the less travelled routes up Rainier.

I was unable to locate any account of her experience with the course.